However, many people think prison should be about rehabilitation; a place to create opportunities for healing and personal transformation otherwise absent in the often highly dysfunctional and damaged lives of many prisoners.

I have been part of the UK prison system since the age of 12, as a visitor to my long-serving father, as an inmate and, since serving my last conviction in 1989, as a workshop facilitator and writer in residence in prisons throughout England and Wales.

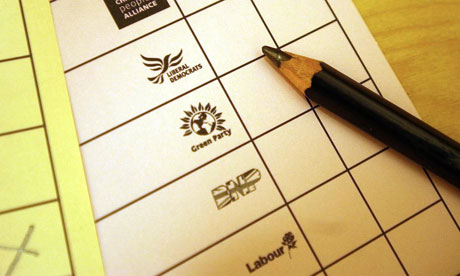

A prisoner’s rehabilitation as a safe, responsible and productive member of society must include the most basic right of democratic process – the right to choose who governs us. To remove this right dehumanizes prisoners. Our streets are rife with blue and white collar criminals, convicted, on bail or simply waiting for the fateful tap on the shoulder. Currently, if individuals are convicted of a crime but not given a custodial sentence they are still allowed to vote; why should they be treated differently from convicted criminals who are locked up?

We must not confuse a criminal conviction and subsequent removal from society (an often essential part of the process of rehabilitation) with a need to remove the essential human right to vote. This was the basis of the recent EU decision to insist that the UK gives the vote to its prisoners. Europe has a wide and varied response to the issue. Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland have no ban on prisoner voting rights. In 13 other European countries, electoral disqualification depends on the crime committed or the length of the sentence.

The 1983 Mental Health Act uses a system of individual assessment to determine a patient’s eligibility to vote. Perhaps, using a similar system, the decision to allow prisoner voting rights could be based on the nature and severity of their crime? A process could be set up that would follow a parallel path to parole procedure as part of tracking a prisoner’s rehabilitation and readiness to re-enter society.

Leave a Reply